Interview with Callum Eaton

CALLUM EATON

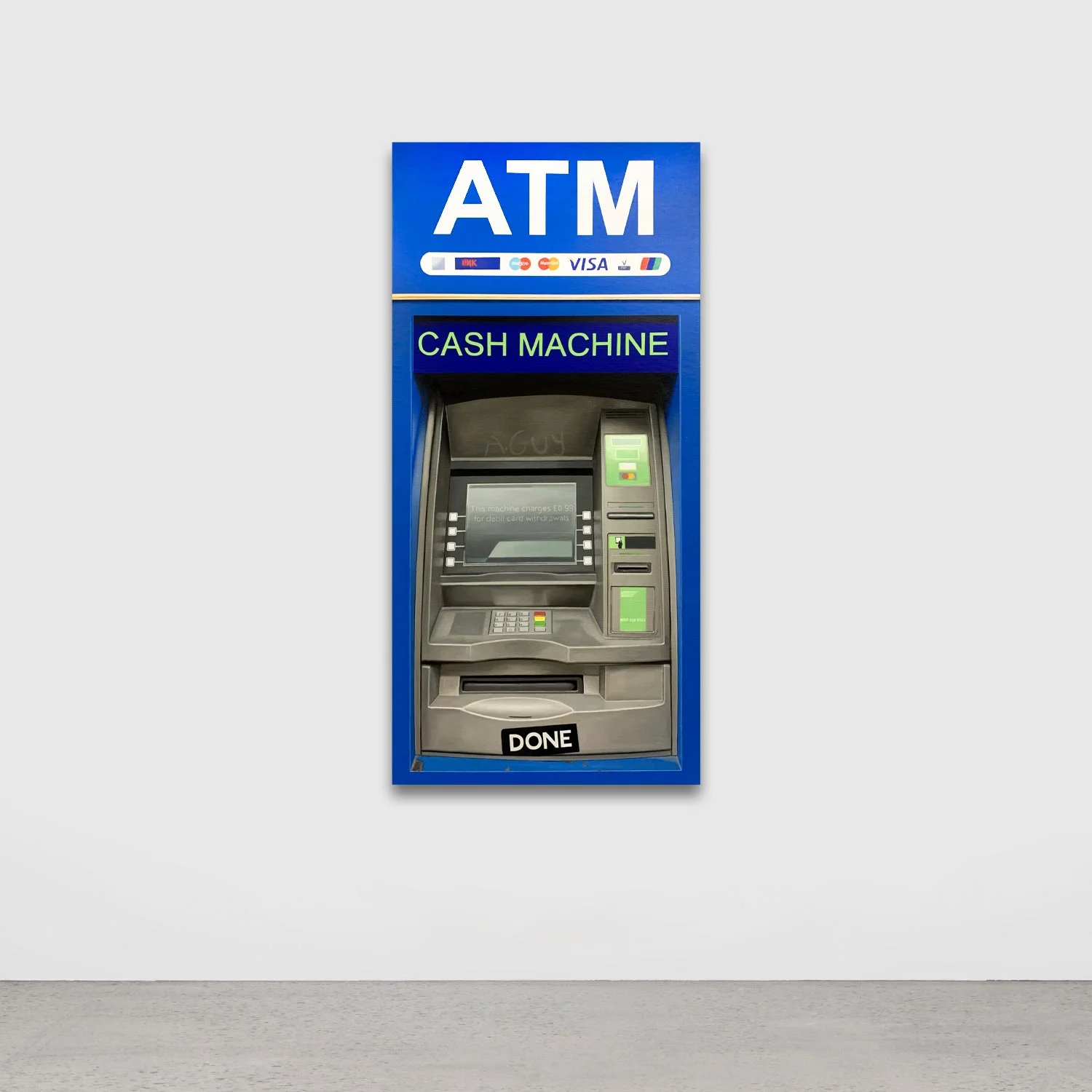

Callum Eaton (b. 1997, Bath, UK) lives and works in London. He completed his undergraduate study in Fine Art at Goldsmiths College in 2019. Eaton’s painting practice combines a mastery of photorealistic rendering with a conceptual critique of contemporary culture and 21st-century society. In his latest body of work, Eaton turns his attention to the almost obsolete ATMs (automated teller machines) that adorn the high streets of the United Kingdom. Once at the cutting edge of capitalist technology and the consumer economy, these cash points are now all but redundant, relics of an age pre-Chip and PIN or contactless payments. Evoking formalism, cubism and the aesthetics of geometric abstraction, Eaton’s hand-painted portrayals invite interaction with trompe-l'œil temptation and false financial promises. In an art world increasingly obsessed with price tags, sales figures and auction results, Eaton’s ATMs serve as a sardonic, satirical reminder that perhaps cash is still king after all.

Photo by David Gwinnutt All rights reserved.

This interview is in partnership with The Mack Art Foundation Residency program who supports emerging artists, offering immersion in the New York City’s art and culture. The program aims to broaden artists' perspectives and connects them with galleries, curators, and collectors.

mackartfoundation.org

INTERVIEW WITH CALLUM EATON BY LAURA DAY WEBB

Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you ultimately decided on a career as an artist?

I was quite late to developing an interest in art. Both my parents are creative, my dad's an architect and my mum teaches textiles, but art was never something I took seriously until I was about 17. We were on a family holiday, and it was raining, so instead of the beach day we'd planned, my parents sat us down and told us to draw something.

I picked a portrait of a man with a beard and set myself the goal of replicating the photo as closely as I could. After a few hours, my parents came back and were genuinely shocked. They even said, “Wow! That’s better than your sister’s!” As the middle child, that really sparked my competitive side and from that moment on, I was off. I decided I wanted to be an artist.

Your work blends photorealistic technique with conceptual depth. How do you balance technical precision with the conceptual commentary in your paintings?

I’m very aware that, as a photorealistic painter, there’s always the risk of the work being seen as no more than technical showing off or just copying. That’s why the subject matter is so important to me.

I studied at Goldsmiths, which was rigorous in its conceptual critique. It almost didn’t matter what you made, as long as you could justify it. So while I’m focused on technical precision, I make sure every painting has a reason to exist beyond that. The realism draws people in, but the idea behind it, what I’m actually painting and why, needs to carry weight too.

What drew you to focus on ATMs as a subject, and how do you see them reflecting broader shifts in consumer culture and technology?

The ATM paintings came from a desire to push photorealism into more trompe l’oeil territory - essentially, tricking the eye. I started looking for subjects that were naturally rectangular or square, echoing the shape of a canvas. I came across ATMs quite quickly, and one of the first paintings was shown at an open studio event I participated in.

A drunk friend, realising the bar only took cash, tried to put his card into the painting. That moment was a revelation. The painting wasn’t just of an object - it was becoming the object. That interaction made me realise there was something really interesting happening.

Beyond the visual, ATMs felt timely. They're slowly vanishing from our streets - symbols of a cash economy in decline. They say a lot about our relationship to money, access, and obsolescence.

Your paintings reference elements of formalism, cubism, and geometric abstraction. How do these influences shape your approach to depicting contemporary objects?

I love these different movements within painting, but I’m not an abstract painter - I’ve tried it, and it felt forced. I was just making something in the aesthetics of abstraction, rather than coming from a genuine place.

Instead, I find abstraction within the objects I paint. An ATM, with its many nested rectangles, immediately reminded me of Josef Albers’ Homage to the Square. Elevators, in their early stages, call to mind Rothko. These visual references emerge naturally in the composition. The beauty is already there, I just highlight it.

In some ways, it’s really the original designers of these objects who deserve the credit. I wouldn’t be surprised if they were familiar with the same art histories I’m referencing.

The ATM series engages with ideas of obsolescence and nostalgia. How do you view the role of sentimentality or irony in your work?

The ATMs and other works I’ve made since definitely ask questions about obsolescence. These once-essential machines, now graffiti-covered and useless, are slowly disappearing. Almost immediately after I began painting them, I noticed how quickly they were being phased out.

By the time I showed the series in Paris in early 2023, nearly half of the ATMs I had painted were gone. Boarded up, ripped from the wall, just trace marks left behind. The paintings became accidental documents, relics of a recent past.

There’s certainly irony in painting something obsolete with such reverence. But there’s also a kind of quiet sadness to it. These objects served a purpose. They were part of the urban landscape. And now they’re disappearing.

In a market-driven art world, your work offers a satirical take on finance and value. How do you hope audiences respond to this critique?

Absolutely. The idea that someone will buy a painting of a cash machine, or even better, a parking ticket for more than the actual fine or the amount of money you’d withdraw is hilarious to me. But also very telling.

The value we assign to things can shift dramatically when placed in an art context. The object loses its function but somehow gains worth. That’s fascinating to me and I hope viewers pick up on the irony, but also reflect on how value is constructed more broadly.

Looking beyond the ATM series, what themes or subjects are you interested in exploring next, and how do they continue your engagement with 21st-century society?

I’m continuing to look for objects that are almost invisible to us; mundane, unexceptional things we interact with every day. I like using oil on canvas, a medium once reserved for grand religious stories or portraits of the elite, to elevate everyday detritus.

By doing that, I hope to shift people’s attention. To say: beauty and importance don’t only exist in the places we’re told they do. Sometimes they’re in the things we pass without a second glance. The biggest compliment I can get for my paintings is viewers engaging with the world around them in a more active way; finding moments in the banal that show them beauty and wonder. If you cant find beauty in your own backyard its not worth finding!

EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS