Interview with Lucy Robson

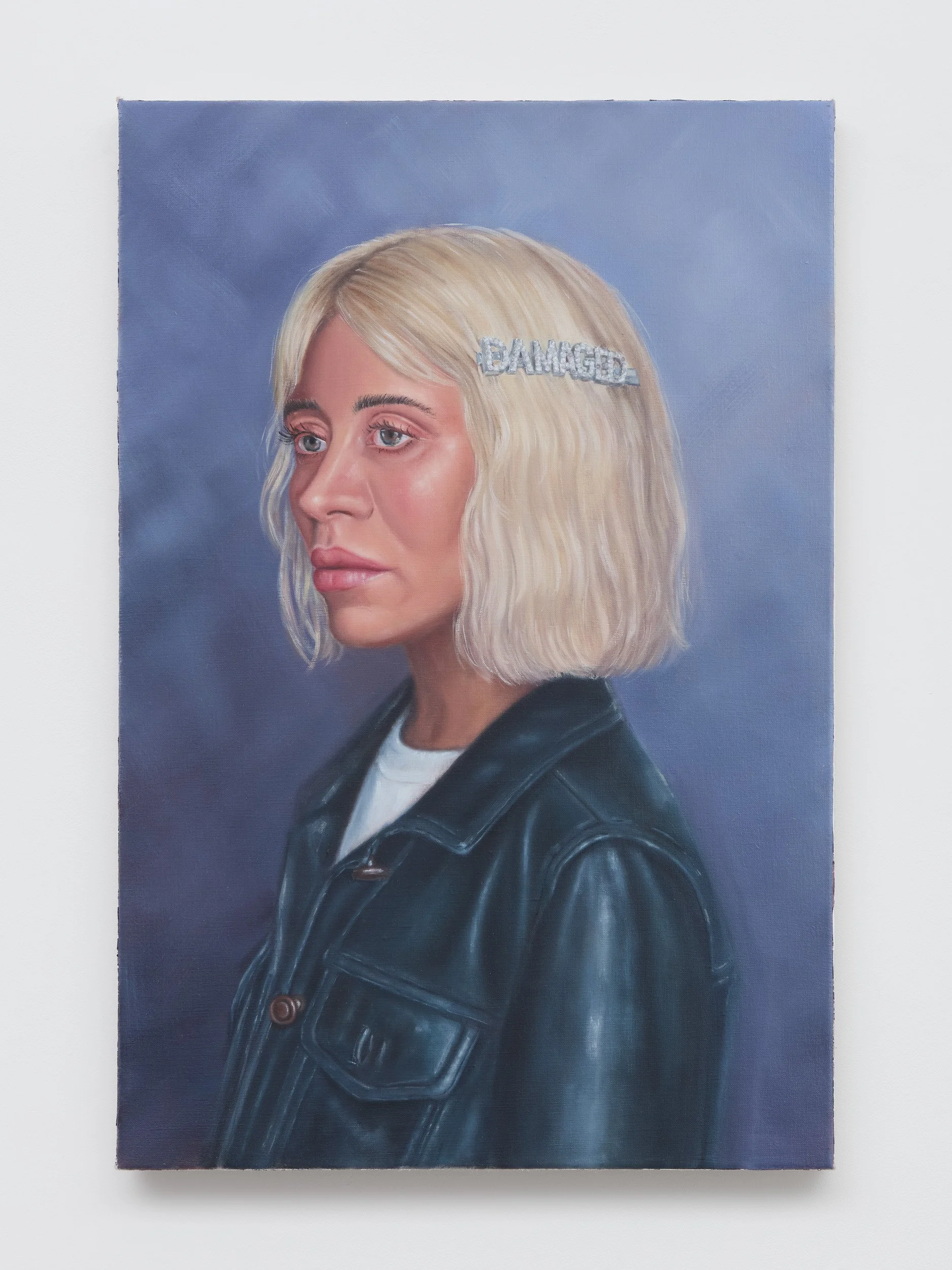

Lucy Robson draws on traditional painting methods and popular culture to explore femininity, desire, and the agony and ecstasy of romantic love. Her work is auto-fictitious, and depicts hyperbolic images that borrow from the aesthetics of cinema, and speak to the complexity of femininity in contemporary culture.

Her background in photography and fashion directly influence her work, which is highly staged and employs filmic devices to bring the viewer sharply to the moment. Lucy’s approach to image-making is rooted in nostalgia and sometimes sentimentality, largely influenced by a long-standing fascination with Girlhood and its growing cultural resonance.

Lucy’s practice aims to marry the surface and the symbol, by combining a deep consideration of the materiality of painting and a desire to uncover the emotional truths within it. She is interested in the fantasy of femininity and the fantasy of love - the double bind of longing and beauty, and terror and self betrayal.

Lucy has shown in London and Cape Town, and is currently in residency in London. Her debut solo show with PM/AM gallery in London recently closed in September. Photo: Aniella Weinberger

INTERVIEW WITH LUCY ROBSON BY LAURA DAY WEBB

Your practice engages with the “visual and material textures of femininity,” particularly through objects often dismissed as sentimental or trivial. How do you navigate the line between reanimating these relics of girlhood and avoiding their fetishisation or nostalgia?

I don’t think I necessarily do avoid their fetishisation or nostalgia, and I try not to shy away from that. The relics of girlhood that appear throughout my work feel almost talismanic to me… they have the power to transport me to a specific time and place. That place is nostalgic and also unsettling, and I try to recreate this feeling in my paintings. Sometimes the work might veer toward sentimentalism, but the way these objects are handled - by me, in the composition - complicates their connotations. In ‘The rest was yet to get me,’ cotton socks are central to the image, however the subject is cut off at the knees. We can only guess what lies outside the picture, but there is a quiet menace in the crop. In other words, nostalgia and fetishisation are countered with equal parts criticality and unease.

In your work, softness operates not as passivity but as a form of intentional tension. Could you elaborate on how you use aesthetic excess: blush tones, delicate surfaces, or ornamental motifs, as strategies of both allure and disruption?

I have this Oscar Wilde quote pinned to my studio wall:

All art is at once surface and symbol,

Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril.

Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.

This marrying of the surface and the symbol is something I think about constantly. I paint layer on layer to create surfaces that are glossy and loaded. In my recent solo show at PM/AM, I wanted to push the temperature of the skin tones as far as I could to gesture at two recurring themes: desire and consequence. The images seek to seduce, and ornamental motifs - a sparkly strap, a reflection in an eye and perfectly lacquered nails - occur throughout. The crop decides the definitive moment, but the textures within the surface invite the viewer in. All these devices - aesthetic excess as you called it - create beauty and pause. Hopefully just enough pause to see the beauty slowly turn on itself.

Your visual language draws from art-historical lineages, from the sensuality of Rococo painting to the uncanny ambiguities of Surrealism. How do you see your work extending, subverting, or conversing with these traditions of representing the feminine?

Like many people, when Rococo is mentioned, Fragonard’s The Swing comes to mind. It is a painting I return to often - for the brushwork, the girlishness and the over-the-top romance - I totally love it! The scene seems frivolous and playful, but of course something more sinister lurks beneath. I’m drawn to Roccco for the fantasy and the promise, but take cues from Surrealist photographers like Francesca Woodman and Claude Cahun when it comes to unpicking those promises. My pictures are more cinematic than surreal, but they speak to the strangeness that manifests within the female psyche when the things that we want - to have and to be - become self-estranging. In that sense, my work borrows from and subverts art historical depictions of the feminine.

Your current body of work interrogates femininity as both ornament and resistance. As your practice evolves, what new dimensions of this dialogue do you see yourself exploring? Are there materials, forms, or narratives you are drawn to next?

My work is autobiographical so in some ways, it reveals itself to me and often mirrors the shifting tides of our time. I am drawn to work that has a distinct narrative power, and this is something I am cognizant of when approaching my practice. To support this, I write extensively as a means of making sense of the work as it unfolds. I frequently think about how I could incorporate writing more into my practice, and recently I’ve been thinking about giving that sense of space and reflection a more literal form—perhaps through a jump in scale.

You have spoken about the connection between beauty, holiness, and emotional pageantry shaped by your Catholic upbringing. How does this intersection between religious iconography and girlish sensuality inform your understanding of power, devotion, and spectacle within your work?

Power, devotion and spectacle are three key tenets in my work. I grew up in a religious and church–going family, and this had a profound impact on the way I approach image-making. It certainly shaped my understanding of beauty as something sacred and performative. I am interested in beauty and feminine archetypes as constructions of a patriarchal world and male economy, and there is no doubt that Madonna was my first encounter with the idealised feminine form (and maybe my first muse). I am drawn to the way holiness is aestheticised, and how femininity is staged within those same terms. And how beauty is inextricably linked to both. Beauty has immense power over us: I try to wield that power to uncover some post-modern truths about the complexities of femininity today.

You’ve had an interesting journey: from co-founding a start up, to working in Corporate fashion in Cape Town, to pursuing an MFA in painting at Goldsmiths in London. How has your experience in the fashion world influenced your practice

It hasn’t been a straight path, and I do wish I had come to painting sooner. That said, my previous endeavours have shaped my practice in so many ways. I studied a BA in Photography, which gave me a rich and extensive visual library. Even then, I had a very good sense of the kind of image that makes my head turn and my mind tinker. Later, working in fashion and manufacturing taught me the importance of having a method surrounding the material process - this has proven invaluable in the studio. And of course, clothing is a recurring motif in my work and it’s no wonder why. I love wearing clothes and I love painting them too.

Your work explores powerful themes like desire, femininity, and heartbreak. How do you approach translating such personal and complex subjects into visual form?

There was initially some fear of and resistance to making such deeply personal work, but I have all but left that behind. My work is me and I am my work. Sometimes that’s helpful and other times I feel slowed down by it. My way of working does feel a bit like reaching into a diary and filtering the pages through the language of cinema. I often think that being an artist makes you acutely aware of the narrative patterns within your own life, and I try not to stifle or inveigle them. I really admire Zadie Smith, and take inspiration from the complexity of her characters: they are wobbling and imperfect, yet sincere and self-aware. That is where I want my work to sit.

SELECTED WORKS