Interview with Lydia Makin

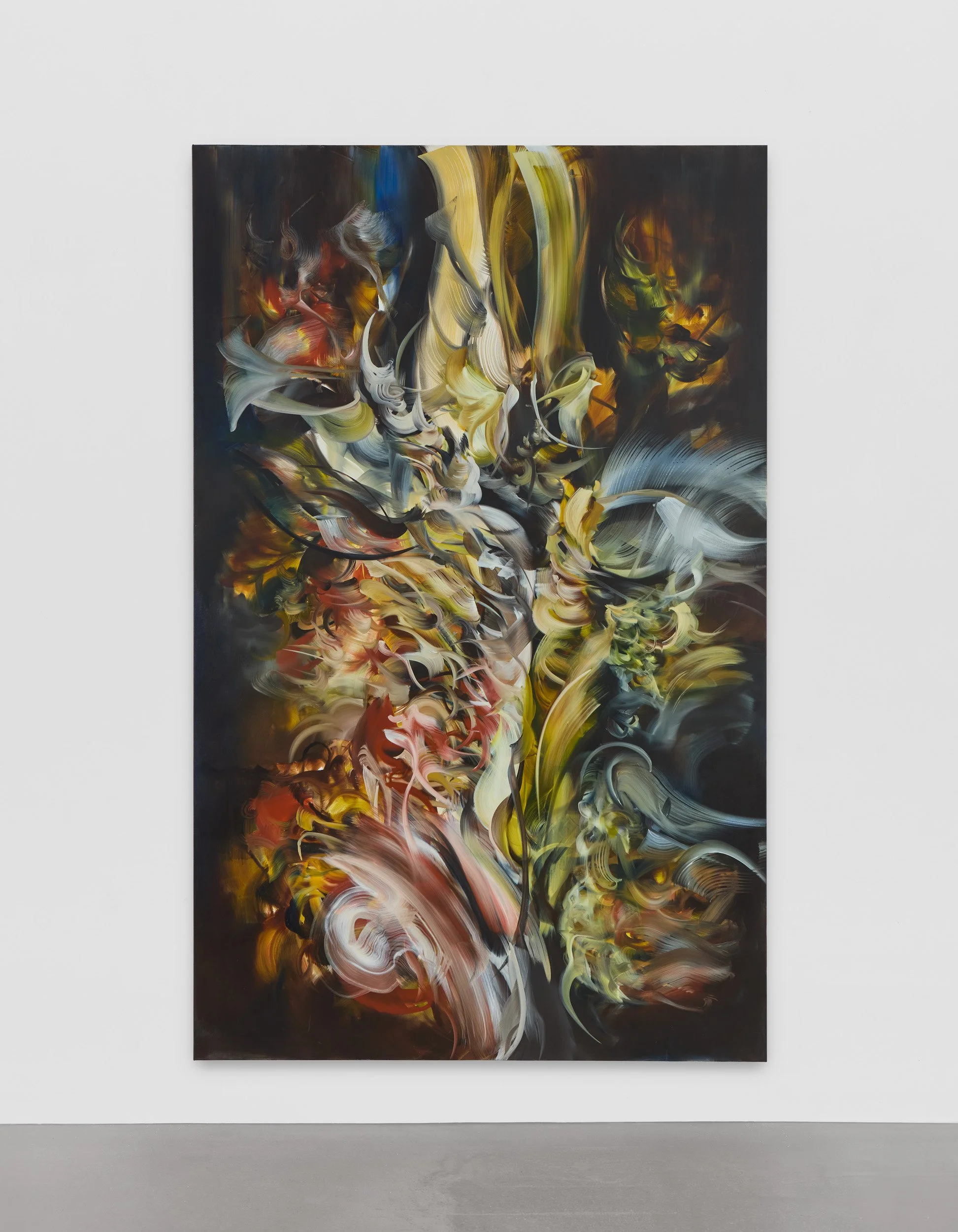

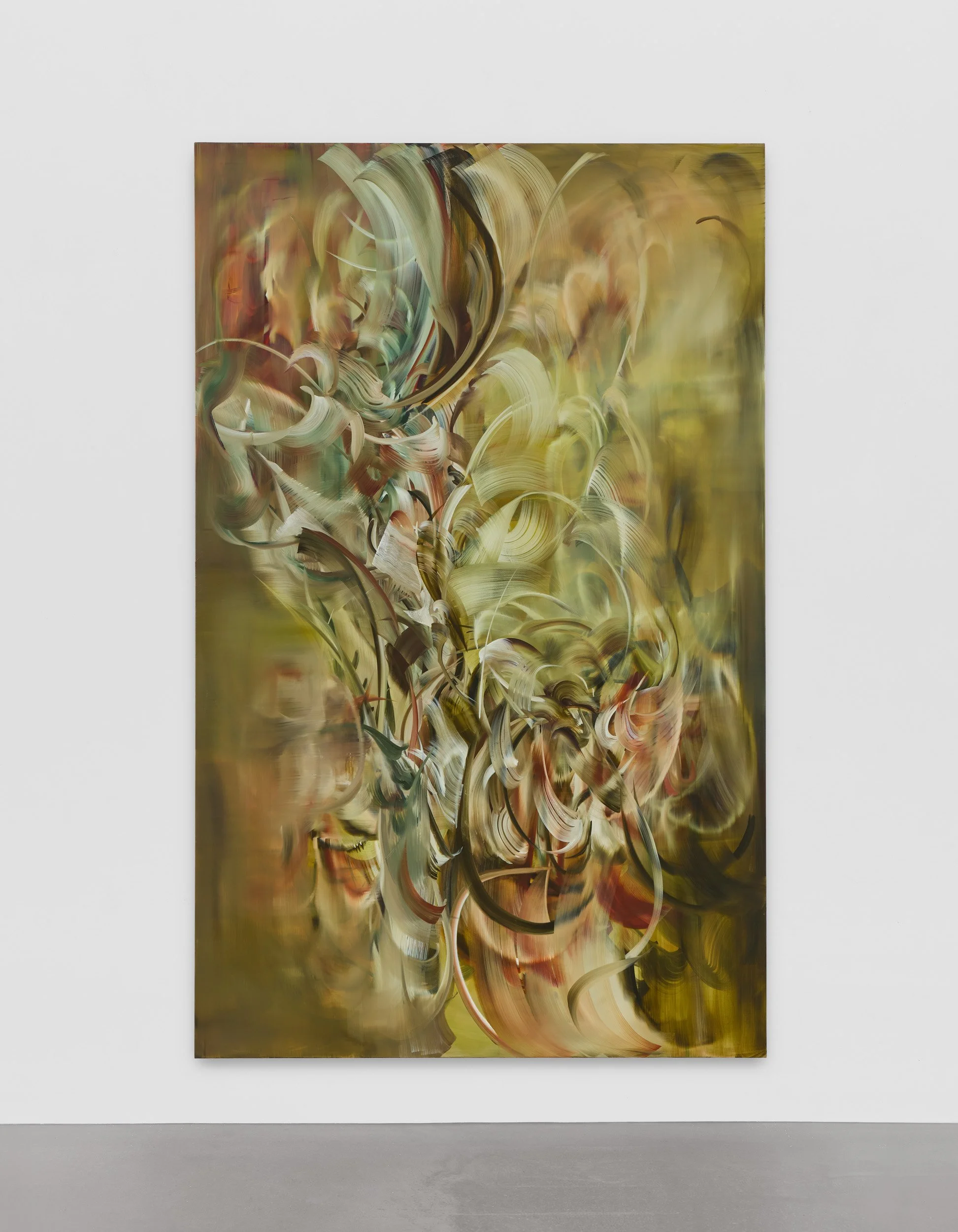

Lydia Makin holds a BA in Fine Art from the Slade School of Fine Art and an MA in Fine Art from the Royal College of Art. She has received numerous accolades, including the Painters Stainers’ Company Scholarship, The Richard Ford Award, and the UCL East Provost Art Prize. Her work has been exhibited in London and Miami, with recent solo and group shows at Studio West, Gallery Rosenfeld, and PM/AM, where she also did a residency.

INTERVIEW WITH LAURA DAY WEBB AND LYDIA MAKIN

Your work integrates both urban and natural impulses. How do you navigate the tension between these two forces and what does their convergence reveal about the spaces we inhabit?

I see my paintings as invitations into the subconscious, where natural and urban impulses rise to the surface as emotional residues — traces of experience rather than literal reference. My process is intuitive: I seek out and respond to moments of discovery as they emerge on the canvas. Living in London, the city's layered energy naturally permeates the work, though more as undertone than subject. If there’s a convergence at play between these external influences, it tends to reveal itself indirectly — through formal tensions: light and dark, structure and fluidity. These oppositions recur throughout the work, not in conflict but in conversation — perhaps reflecting the inner landscapes we each navigate.

You speak of a 'third space’ within your practice. Could you elaborate on what this space represents both philosophically and visually?

I understand the ‘third space’ in painting as a liminal zone — a place where memory, emotion, and environment intertwine; where thought gives way to feeling, and intention dissolves into instinct. Philosophically, it’s tied to presence and embodiment, a porous state between self and world. My process is uncertain, precarious. There’s tension in the not-knowing — but also a charge, a quiet thrill, as the image unfolds and finds its own rhythm.

Your compositions seem to carry the energy of spiritualist abstraction and post modern mysticism while also feeling rooted in futuristic sensibility. How do you situate your work within or beyond these traditions?

If the work resonates with certain traditions, it’s likely because of shared concerns — with the immaterial, the sensual, or the symbolic. Though I understand why those connections arise, I’m not consciously aligning myself with any one lineage. The paintings emerge from lived experience, shaped through the act of making. They exist somewhere between — or perhaps beyond — categories, and I’m comfortable leaving that space undefined.

Artists such as Caravaggio, Raphael and Goya have informed your practice. In what ways does the theatricality of these old masters resonate in your work, and how do you re interpret it through a contemporary lens?

Encountering Goya’s Black Paintings at the Prado was a formative experience. In his work, reality feels blurred and destabilized, yet utterly alive. What struck me most was the raw urgency of his brushwork — a visceral surrender to the medium, as if he were channeling something beyond himself. That depth of presence is something I strive for in my own practice.

With Caravaggio, it was the way darkness functioned not just as background but as atmosphere — carrying weight, presence, even drama. From Raphael, I’ve always been captivated by the way movement breathes through the folds of fabric.

I don’t seek to directly reinterpret these reference points, but they inform the cadence of my process, surfacing organically as I work.

You have expressed a desire to create something new and unexpected in each piece. How do you cultivate this sense of discovery while remaining grounded in a coherent visual identity?

While there is a thread that links my paintings, it’s not something I consciously impose. It arises naturally from core interests that have shaped my practice over many years — namely, bodily rhythm and gestural flow.

Painting is limitless and expansive in its nature. I see my paintings as their own living, breathing life force. For that vitality to emerge, each painting must undergo a process — one that can’t be repeated. I couldn’t recreate the same image twice, even if I tried.

The scale of your paintings creates an immersive, almost overwhelming experience. What role does scale play in your effort to alter the viewer’s perception or emotional state?

I still remember seeing Lee Krasner’s The Eye is in the First Circle at the Royal Academy during my first year at the Slade. The sheer physicality of the brushwork left a deep impression — it revealed how large-scale painting, when done with conviction, can be profoundly affecting. That experience has stayed with me.

For me, the beauty of painting lies in its ability to express the unsayable. When this quality is amplified by scale, the result can feel almost otherworldly — something that shifts perception and unsettles the boundaries of language. Words often feel too narrow for what painting can hold. At its best, large-scale painting doesn’t just surround us; it challenges us with its vast, unbounded complexity.

WORK HIGHLIGHTS