Interview with MAESTRO

MAESTRO

MAESTRO is a hyper realistic, black-and-white artist based in Santa Barbara, California. Originally from Valencia, Spain, MAESTRO received technical training from the Stuart Weitzman School of Design before beginning a dynamic career as a visual artist and architect. MAESTRO has worked for firms such as the Bjarke Ingels Group (B.I.G.) and had artistic collaborations with many LA-based creatives, including DOPEHAUS STUDIO and NeueHouse Hollywood. His work has been shown, among other venues, at the Charles Addams Fine Arts Gallery, the :iidrr Gallery in Manhattan, Graffiti Library in Los Angeles, The Victorian in Santa Monica, Just Another Gallery in Philadelphia, and the Sullivan Goss gallery in Santa Barbara. His first solo exhibition, “LOADING” opened at the HOMME Gallery in Washington D.C. on April 3rd, 2025.

INTERVIEW WITH MAESTRO

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came to be an artist?

I was born in Valencia, on the Mediterranean coast of Spain, so I was exposed from an early age to a lot of natural beauty, as well as the kind of art and architecture that has stood the test of time. I suppose I was always interested in things that last, especially objects that add elegance to the world in one way or another.

My father was a painter, but it wasn’t his profession. He encouraged me to draw when I was younger and occasionally I would help him paint the background in one of his pieces, but I didn’t consciously consider art as a profession until I was an adult. I ended up pursuing architecture which, looking back, I think I always treated as a kind of artistic practice. I studied at the University of Pennsylvania and the polytechnic school of architecture in my home city, then built a freelance design practice, developing the skills that would eventually lead me back to art.

Congrats on your solo show at HOMME Gallery! As a part of the exhibition, viewers are able to interact with the work digitally via QR codes. Can you share a little more about the digital aspect of the work? Is there a particular effect you hope a viewer will take away from it?

Thanks very much! It was surreal to see an entire gallery filled with my work.

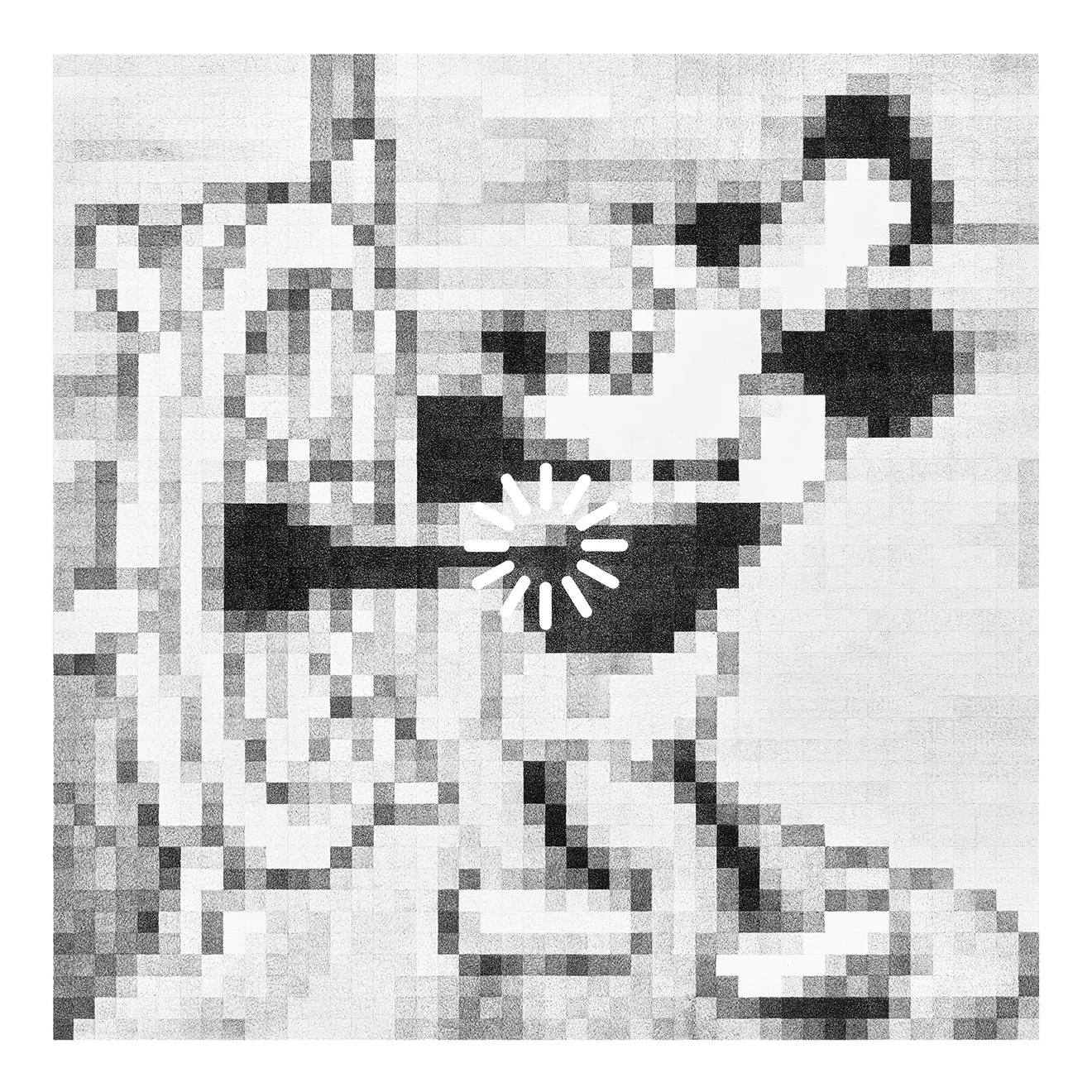

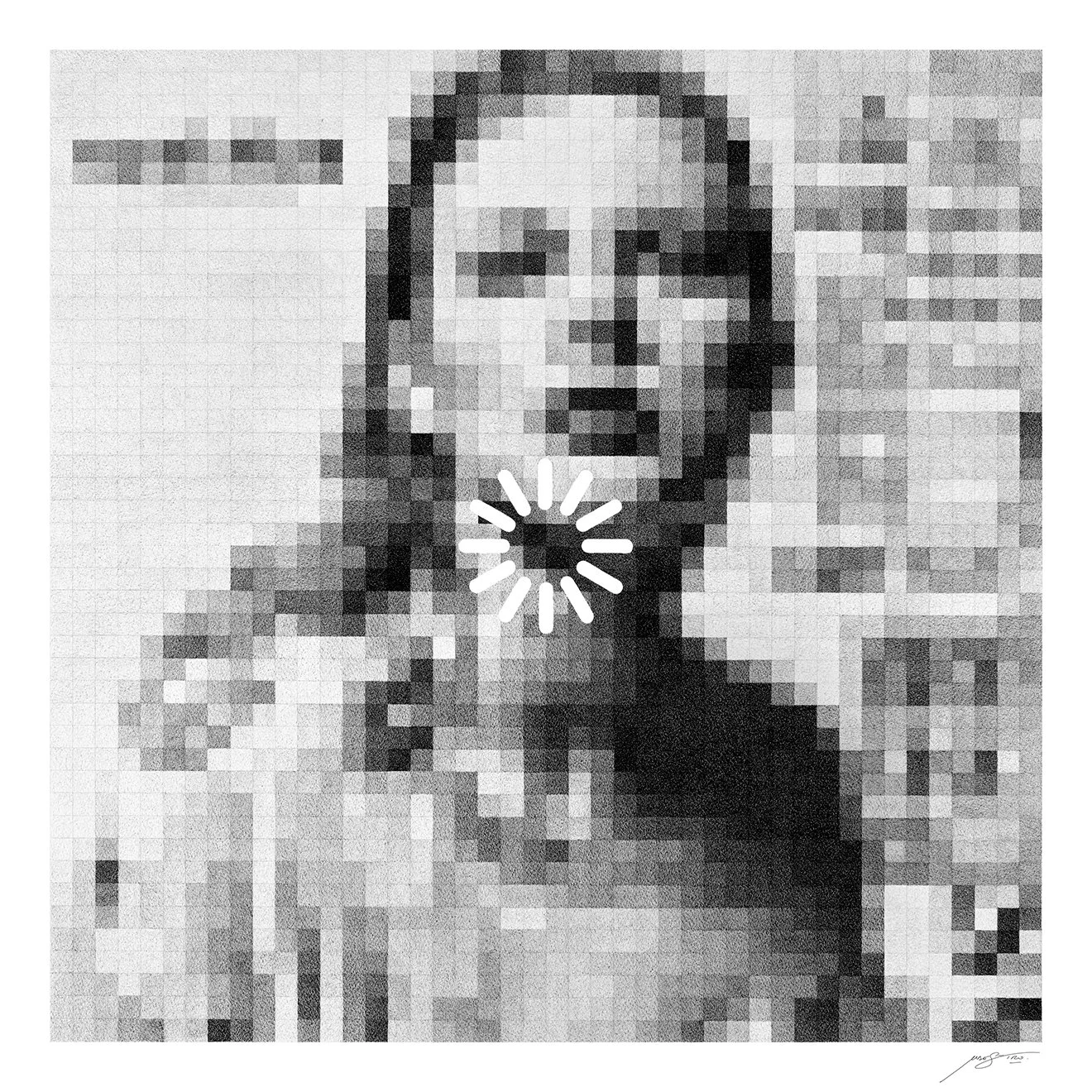

The pen-and-paper drawings are the centerpiece of the exhibition, but I have also developed an augmented reality element alongside them in the form of digital cityscapes. The cityscapes are derived from the gradient of black-and-white pixels in each drawing, and can be accessed in the gallery by any viewer with a smartphone.

While my pen-and-paper works are concerned with seeing the iconic past through the lens of the present, my experimentation with augmented reality is about looking into the digital future. In general, my art critiques our obsession with digital consumption, especially as a way of relating to the past, but I am not against technology itself—nor do I think it’s going anywhere anytime soon. There is a lot of space to play with augmented reality, and I like to be playful with my art as well as serious.

Ultimately, I see each pixelated piece of mine as a blueprint for a possible digital world. Just as each iconic “loading” image or figure represents a broader configuration of meaning, each physical configuration of pixels has the potential to become its own digital landscape—a potential that reflects the excitement and uncertainty of our technological future.

For this show, I think I was able to achieve the immersive effect I wanted: for the viewer to feel like they’d stepped into a pixelated world.

Your work is known for the pixelated grid of cultural imagery, usually done in black and white. How do you decide on the source imagery?

Pixels are something of an obsession at this point in my life. My drawing of them first grew out of frustration—with certain aspects of technology, with the pace of contemporary life, etc.—but quickly became a meditative exercise and an expression of my relationship to control, order, and structure. I feel a bit like I am both reclaiming and losing something as I draw them—possibly time.

Pixels are essentially digital atoms. Every image you’ll ever see through your computer or phone screen consists of them, just in a greater or lesser concentration. My work plays with that concentration, asking how many pixels are sufficient to make an “iconic” subject legible to a contemporary viewer. The subjects themselves are selected for their timelessness—their capacity to fascinate and the magnitude of their cultural impact. My focuses right now include iconic cultural figures, historical events, and art objects of the past.

What role does your studio space play in your practice?

My studio space at this time is my home. My wife is a writer, so we are both creatives. We have a one-year-old baby, two ragdoll cats, and a small army of plants—all packed into a one bedroom apartment. It’s total, beautiful chaos.

Half of the house is dedicated to our creative work, but it’s still a pretty tight fit. My wife writes on the bed, on the couch, pretty much wherever she can. Since my work requires a firm, flat surface, the table where I feed my daughter is the table where I draw.

I hadn’t thought much before about how that affects my practice, but there is probably a relationship between the precision of my work and the disorder of my life in general. When I sit down to draw, it’s a little bit like sitting down in the eye of a storm—everything around me becomes quiet. There’s no color, no improvisation, just the black pen in my hand, the white paper in front of me, and the pixelated image in my mind. It’s soothing, empowering, and temporary—ultimately an illusion. Whether its cats, babies, or digital images, life can’t really be controlled, and my art plays with that concept directly.

I look forward to the day I have my own studio—it’s a major dream of mine, as is opening a gallery. But in the meantime I wouldn’t trade what I have. I love being surrounded by my family and the little life we have built together.

If you could study with an artist past or present, who would it be?

I’d say either Michelangelo or Bernini. I’m fascinated by most Renaissance and Baroque artists and I would have loved to live during a time when art patronage was a thing. So I’d choose one of those two, but for completely opposite reasons.

Michelangelo was a master of several mediums. I think I’d enjoy his snark on a personal level, and I’d love to get a class from him on painting. Though his sculpture of Moses is one of my favorites of all time.

Bernini is someone I admire for his storytelling and for being a master of a single material—I think it was Carrara marble. He was multi-talented, too, but for a period he stuck with one medium and took it as far as it could possibly go. That’s something I aspire to emulate at this point in my career. I want to be recognizable for excellence in my chosen medium, and for my work to stand on its own conceptually.

FEATURED WORK