Méïr Srebriansky in Conversation with Anna Mikaela Ekstrand

Ayana Evans

"Presenting the Black Avant Garde: a Tribute to Senga and Maren" 2019, Ayana Evans and Tsedaye Makonnen, timed tripod image shot by the artists.

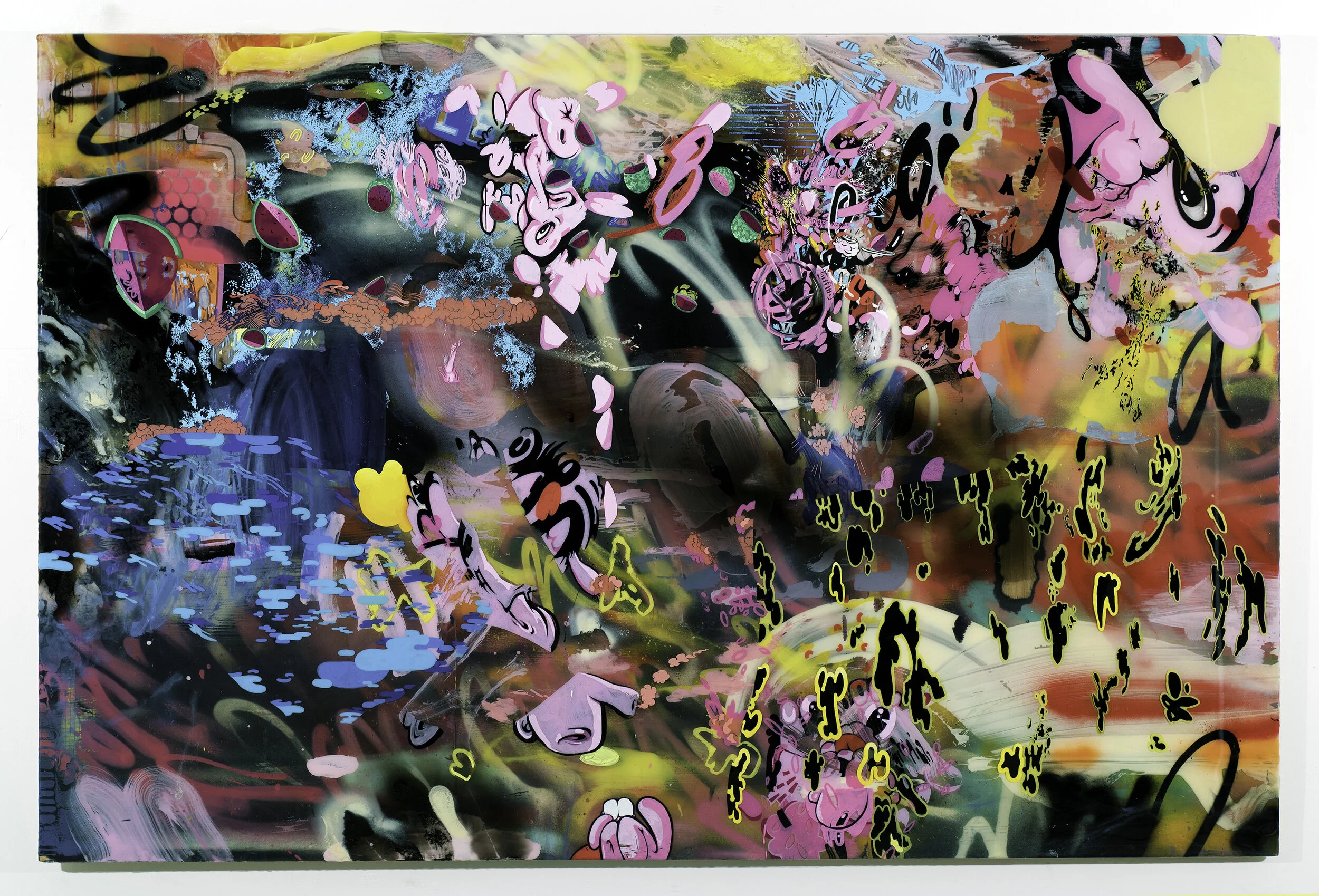

Méïr Srebriansky (b. 1976 in Strasbourg, France) is an abstract painter based in New York City. He earned his BFA from École supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Strasbourg. In France, influenced by French and American New Wave cinema, he painted realism. Working with blurred photographs in his series “Wasted Pictures” led the artist to explore abstraction. Shapes often derived from his figurative drawings, and colors, guide his labor-intensive process driven by popular culture, science, and the depths of his own imagination.

He corresponded with guest juror, Anna Mikaela Ekstrand to discuss his influences, challenges, and triumphs in his practice.

Anna Mikaela: What would you do if you were not an artist?

Méïr: A mix between a religious scholar, a psychoanalyst (I really love psychoanalytic literature, but more as literature than a belief system), and a scientist, or a full-time father. I enjoyed studying science before transitioning to art school, although, I usually lost focus and started to draw in class. I love what I do and art is a big part of my identity so it is hard to speculate without that referential.

Anna Mikaela: Some years ago you shifted from painting in oil and acrylic on canvas to incorporating resin in your practice. Why did you decide to shift materials?

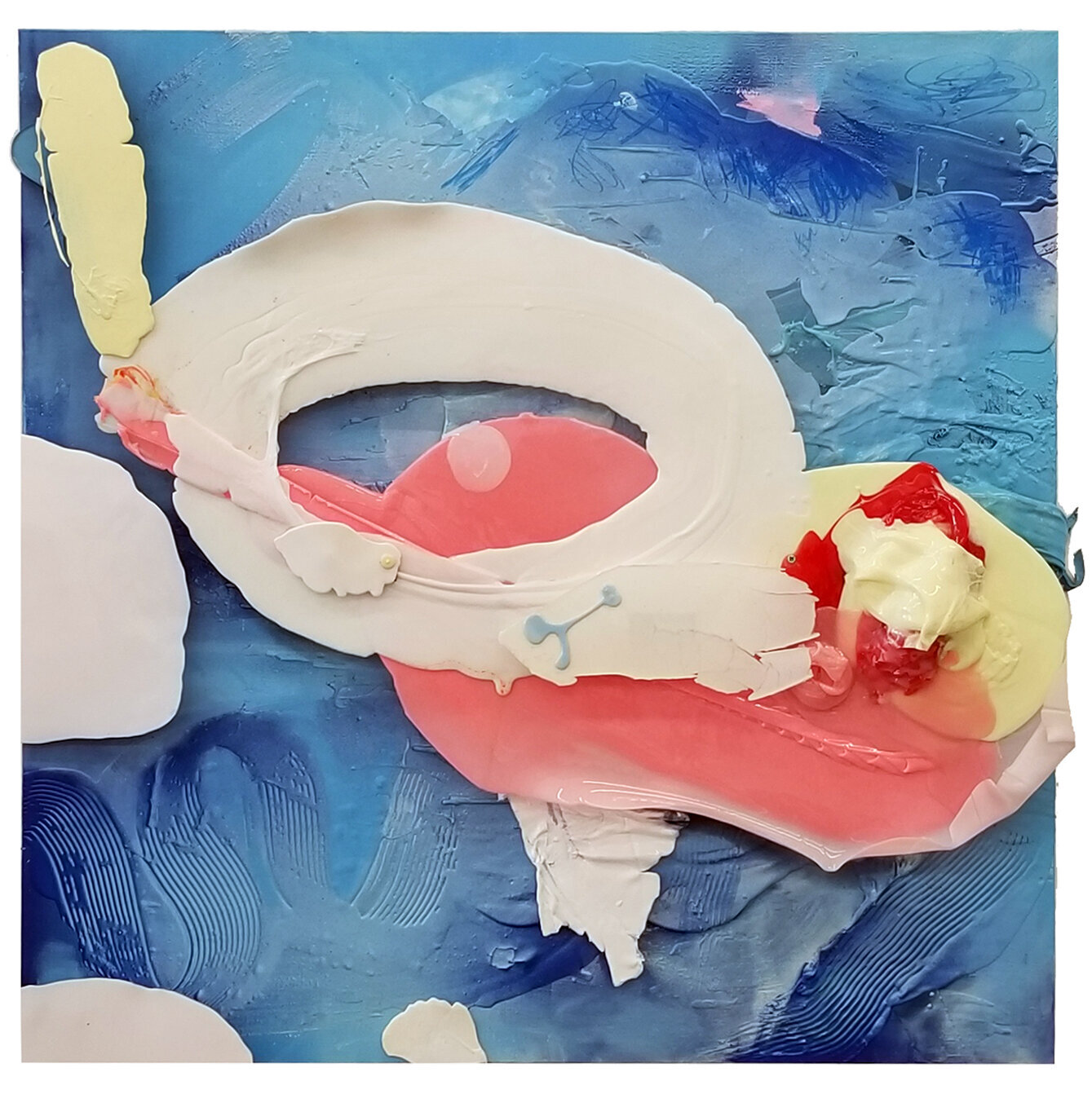

Méïr: My fascination with the physicality of painting pushed me to develop ways to break down its parts and emphasize them in the physical world. When I look at a painting, its brushstrokes, the painting technique, and the small parts that help materialize the thoughts of another human being is what first pulls me in. When I see a painting I do not primarily focus on the image but on the way it is built. My desire is to taste it, eat it. Based on this mode of consumption, I wanted physicality to be more present in my work so I developed protruding shapes that can be likened to giant brushstrokes. Sensual forms that I could apprehend physically, that could be eaten by my mind. Imagine being able to zoom in a thousand times on a painting to contemplate, touch, and feel the landscapes made by the strokes of a painter's hand. That desire is the basis of my resin work. My move from France to the United States pushed me to embrace a new language, a new culture, and finally citizenship – this experience might also explain why my work has become more physical, grounded, and direct.

Anna Mikaela: What challenges did you face working in this new material, how long did it take for you to get a handle of it?

Méïr: Resin introduced me to new limitations such as gravity, curing time, and chemistry. When I embarked on this journey I ordered all sorts of different resins, polyurethane, polyacrylic, acrylics, and silicones from chemical companies online in order to research chemical reactions in my studio. Engaging with these new materials forced me to change my approach; pouring resin is obviously not the same as using a pencil or brush. I had to learn how the material behaves and how I could paint or draw with it, and not only using it as a seductive varnish. That said, I fully embrace the kitschy component of the glossiness and navigate around its borders as a signifier. Also, I had to figure out the practical application of the material: what sticks and what does not, what makes it bubble or blobby, and what makes it flat. The weirdest challenge was moving from the verticality of painting to creating works on the floor, horizontally, which made me feel a bit like a bird.

Anna Mikaela: Shifting to a bird's eye view, clever! What is the most complicated artwork that you have made?

Méïr: Not the most complicated, but Sploosh is a small piece that was technically advanced in my exploration of the new material. It took gallons of resin - trial-and-error - for me to create a piece that I deemed good. I tried to push the boundaries of what I was able to do with poured resin and my aim was to achieve intricacies. I had to pour using two hands and I devised a choreography of sorts to quickly distribute the material across my canvas. The curing time is extremely fast between liquid to solid-state. Once the resin is solid it cannot be softened again. When pouring, there is very little time to think so it is spontaneous. I really have to be present and in the moment to not mess it up. Therefore, acceptable results are reached within a very little margin of time, which makes it exciting and terrifying. Preparing the material and surfaces takes time but the actual pouring is fast and focused.

Anna Mikaela: What are your tips for artists who are experimenting with new materials?

Méïr: Find joy in experimentation. Be ready to fail and waste both material and time. Have the mindset of a researcher. Keep trying.

Anna Mikaela: All of your resin works are not protruding; some are more flat like ‘Underneath.’ Can you tell me about your creative process and the relationship between inside and outside, or over and under, as it were, in this work?

Méïr: Just because something is under the surface doesn’t mean it isn’t there. Layering is a big part of my process and it is also how my mind functions. Similarly to a person’s identity that is built up by layers of memories and experiences, a painting is built up by many invisible brushstrokes. Like most of my work ‘Underneath’ is built up by a collection of layers – using power tools, a hammer, a blowtorch, I punctured the surface making the layers visible. In all my work I try to build a syntax in which every element is carefully considered may it float in a chaotic environment. Matte versus glossy, flat versus 3D, carving versus drawing, protruding, precision versus free expression. Underneath and the other work where I punctuate is a nod toward limitations, we have moved beyond certain limitations in the history of painting, but others exist still. I'm making pieces that look like floating drawings. I can get rid of a canvas and be facing new limits. Limitations are inherent to our relationship with the real. The act of painting is a direct dialectic with it.

Anna Mikaela: Your work is multi-layered, multi-dimensional, and your process is measured – it can take you up to a year to finish an artwork. What do you do when the going gets tough?

Méïr: I switch to a different type of medium to fill the void, to deter my anxiety. If I am working with resin I start to draw. If I am working with oil paint I transition to resin. The most important thing for me is not to wait for inspiration even if I feel lost, but to keep on working no matter the result. Doing. Ideally at least, but let's be honest I often get stuck, at a loss, staring at a wall trying to see what's next and could potentially finish the sentence I'm trying to express.

Anna Mikaela: Your work has been included in seven group exhibitions and three art fairs this year. Congratulations. What are your tips for artists who want to show more?

Méïr: I got out of my comfort zone. I happily and genuinely lived under a rock for a long time and was satisfied with a loyal following. I was also working on other commercial time-consuming projects so I had to deal with a different schedule. Some years ago I decided to put myself out there, or at least my work. As it turns out, it has worked out fine and I am thankful for the exhibition opportunities that have come to me, the artists I have met on the way, and the people who engage with my work.

Anna Mikaela: Silk-screen printing! Yet another new material and practice you have plunged straight into. You worked with Gary Lichtenstein Editions to realize this limited edition series. He is a legend that has worked with Marina Abramovic, Robert Indiana, Ken Price, Joanne Greenbaum, Jessica Stockholder, Alex Katz, Dave Navarro from the Red Hot Chilli Peppers and the list goes on. How was it working with Gary?

Méïr: It was great! I love working with Gary because he is also an artist and an amazing craftsman. He took my work very seriously and helped me open my mind to the potentials of the new medium. He also has a very unique New York personality – he is fun, sociable, and always has a wild story up his sleeve. Our studios are on the same floor at Mana Contemporary, he, his business partner Melissa, and their team of assistants have always been extremely welcoming, friendly and helpful. It is always humbling and rewarding to work with a master.

Anna Mikaela: Finish this sentence: “Painting is…”

Méïr: To paint.